Therefore it is our duty to thank You, and to praise, glorify, bless, sanctify and give praise and thanks to Your name. Happy are we, how good is our portion, how lovely our fate, how beautiful our heritage. Happy are we who, early and late, evening and morning say twice each day –

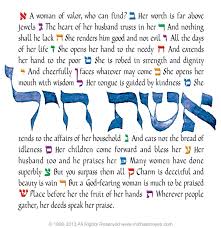

שמע ישראל ײ אלהינו ײ אחד

Listen Israel: the L-rd is our G-d, the L-rd is One.

Blessed be the name of His glorious kingdom for ever and all time.

Love the L-rd your G-d with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your might. These words which I command you today shall be on your heart. Teach them repeatedly to your children, speaking of them when you sit at home and when you travel on the way, when you lie down and when you rise. Bind them as a sign on your hand, and they shall be an emblem between your eyes. Write them on the doorposts of your house and gates.

During periods of persecution the joyful lead-in to the Sh’ma serves as a bold refutation of our perilous conditions. Our freedom to express our faith through observing the Shabbat, reciting the Sh’ma, and studying Torah is a perennial target of our oppressors; their constant goal is to separate us from the core of our faith in the One True G-d. Yet whether we live our days harassed or welcomed, we must cling to these precious foundation stones with heartfelt delight and gratitude.

“Listen Isra’el: the L-rd is our G-d, the L-rd is One.” The Sh’ma, known to the youngest child, and often the last words spoken prior to death, is the timeless affirmation of our faith.

“Blessed be the name of His glorious kingdom for ever and all time.” This is spoken quietly, practically inaudibly – with the only exception during Yom Kippur when we are released to declare these words in our loudest voice. There are various teachings for this practice, all of which provide deep insights to our ancient culture.

Immediately following the Sh’ma, the v’Ahavtah begins with a mandate to love HaShem completely. The Ḥazal teaches that Avraham loved HaShem with all his heart; that Yitzḥak loved HaShem more than his own “נפש“ (soul), as demonstrated in the Akdeidah; and that Ya’akov loved HaShem “מאדך,” a word which is difficult to translate. Frequently translated into English as might, strength, or resources – the concept is “everything, and more; and still more; and then some.”

The v’Ahavtah extends the Sh’ma across generations; we are commanded to teach our children “repeatedly … when you sit at home … when you travel on the way … when you lie down … when you rise.” Surpassing mere transfer of information – this is an imperative to live so that our children grow to love HaShem.

The v’Ahavtah finishes by drawing our attention to “a sign on your hand … an emblem between your eyes … [written on] the doorposts of your house and gates.” The mitzvot of laying t’fillin and of hanging mezuzot are based on these commandments. We bring our daily lives into alignment with HaShem through repeated physical acts of obedience, and it is through His great compassion for us that He bestows us with an abundance of mitzvot.

The prayers which follow the v’Ahavtah are laser-focused on Hashem: He is our Eternal King, beyond infinity yet within every individual. We sanctify His Name and also those through whom His Name is sanctified – a reminder to guard against taking G-d’s name לשוא (casually), plus quiet homage to those who have and will defend His Name through Kiddush HaShem.

His Salvation gives us assurance that we will one day see Him known by all nations. We eagerly await the day when He redeems us from exile. We yearn to see the rebuilt Holy Temple and to once again proclaim Him to all creation as the One True G-d. We imagine preparing the daily sacrifices in the rebuilt Holy Temple – we now are ready to study those very offerings.

Recap:

We’ve learned that the Mah Tovu prayer, which we sing individually as we enter the synagogue, exhorts us to leave all our personal joys and sorrows behind so we may worship without distraction.

The Adon Olam pulls us into a greater awareness of Hashem as the G-d of all the vastness of infinite creation – yet also as our personal ever-present G-D.

Yigdal then directs our attention to Israel’s unique connection with Hashem. He is the G-d of Israel; revealing Himself to us in ways the nations do not yet see. The familiar rhythms of the Birkat HaShaḥar reinforce our unique relationship with HaShem as interconnected individuals within the Nation.

The Akeidah anchors us to the very beginning of Judaism – the faith of our father Avraham.

The Sh’ma and the prayers completing this section of services summarize Israel’s declaration to the nations of the One True G-d and Israel’s hope of redemption – an anchor during our darkest days of persecution.