The Akeidah is our first Torah reading during Shaḥrit services but the second Torah reading of the morning. The Blessings Over the Torah, said at home during our early morning prayers, officially begins our daily Torah study and also sets the expectation that we will continue in further Torah study throughout the day. Since it is essential to directly connect an activity with the blessing for that activity, we immediately follow The Blessings Over the Torah with a Torah reading (the Birkat HaCohanim) followed by commentaries from both Mishna and Gemara.

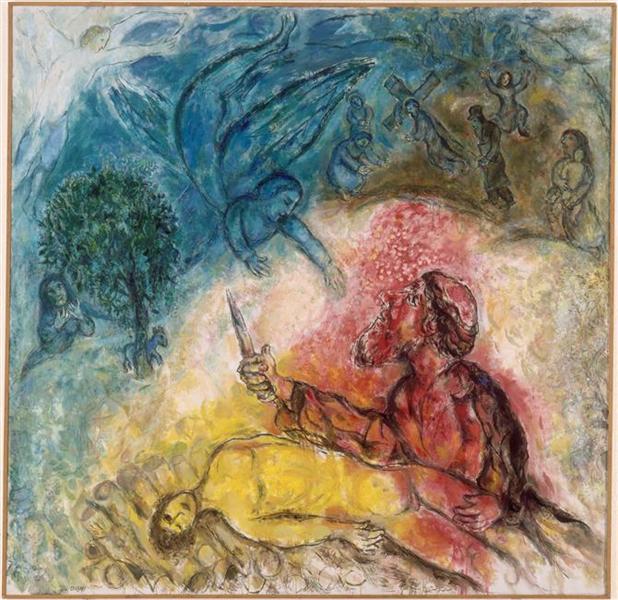

The Akeidah, also known as the Binding of Yitz’ḥak, hinged on Yitz’ḥak’s willingness to allow his elderly father to sacrifice him on the altar built on Har HaBayit (Mount Moriah). Yitz’ḥak was a man in his 30’s at that time yet all indications are that he freely gave his cooperation. He understood and embraced the singular purpose given him; Yitz’ḥak was ready to die.

The Biblical account of the Akeidah does not focus on Yitz’ḥak but on his father. Why is our attention drawn to Avraham? Yitz’ḥak was the heroic one – right? Yes, but Avraham’s task was vastly different from Yitz’ḥak’s – and far more difficult to endure.

HaShem commanded Avraham to kill his son. There may be merit in being willing to die, to sacrifice your life for others – but how do you embrace the thought of sacrificing someone you love, of killing your only child? When HaShem called Avraham to take “your son, your only son, Yitz’ḥak, whom you love . . .” He was drawing Avraham into an agonizing act of faith, an act which could only be misunderstood and condemned by everyone he knew.

Through His harsh directive HaShem allowed Avraham a glimpse of His own agony, of the immense price He paid for eternal Israel. Avraham was convinced his son was about to die; Mashiaḥ Ben Yosef actually dies. To truly engage with the Akeidah is to be emotionally exhausted.

Our response, entitled “Accepting the Sovereignty of Heaven,” dates from a period of persecution during which Shabbat observance and Torah study were forbidden. It is poignant to realize that our challenge to be consistently observant in all we do, both public and private, was written at a time when we were forced to practice our faith in secret; at a time when many instead chose Kiddush HaShem (martyrdom). Faced with the enormity of this challenge of faith, we pour out our hearts:

“What are we? What are our lives?

What is our loving-kindness? What is our righteousness?

What is our salvation? What is our strength?

What is our might? What shall we say before You,

L-rd our G-d and G-d of our ancestors?

Are not all the mighty like nothing before You,

The men of renown as if they had never been,

The wise as if they know nothing,

And the understanding as if they lack intelligence?

For their many works are in vain,

And the days of their lives like a fleeting breath before You.

The pre-eminence of man over the animals is nothing,

For all is but a fleeting breath.

“Yet we are Your people, the children of Your covenant,

the children of Avraham, Your beloved, . . .”

Notice how we plummet to abject insignificance and then abruptly soar to mighty purpose. These sudden shifts should begin to feel familiar as we move from the Mah Tovu to the Adon Olam, Yidgal, Birkat HaShaḥar and now the Akeidah.

As our perspective repeatedly swings between the miniscule and the infinite, from the individual to the Nation to the Ein Sof, we sense the rhythm of worship. To those new to Judaism this may feel more jolting than rhythmic. Yet over the months and years as we incorporate these prayers into our daily lives these seemingly incongruous perspectives somehow reconcile; we continue next with the preliminary prayers for the Sh’ma.